Jonathan A. Obar, PhD is an Associate Professor in the Department of Communication & Media Studies at York University. His research and teaching focus on information and communication policy, and the relationship between digital technologies, civil liberties and the inclusiveness of public cultures. Academic publications address big data and privacy, online consent interfaces, corporate data privacy transparency, and digital activism.

Data sets for training artificial intelligence (AI) may be filled with information obtained without meaningful consent. Whether an organization collects data directly from users or from another organization, ensuring the meaningful consent of the individuals represented in the data is vital. As the Canadian government debates Bill C-27, and questions the future of ethical AI, this issue must be a priority.

Developers may attempt to train AI systems to help a store sell products, a bank to determine mortgages, an insurance company to quote premiums, the police to identify suspects, or a judge to calculate recidivism rates. In any of these cases – and many more – if the people whose data drives these systems didn’t consent to their data being used in AI development, this is a potential violation of civil liberties. Furthermore, the lack of oversight associated with a lack of meaningful consent could lead to harms associated with big data discrimination.

Writing about problematic data collection and use by AI developers, Kate Crawford, a leading AI scholar, warns:

The AI industry has fostered a kind of ruthless pragmatism, with minimal context, caution, or consent-driven data practices while promoting the idea that the mass harvesting of data is necessary and justified for creating systems of profitable computational “intelligence” (p. 95).

When someone shares a photo online, do they agree the photo can train AI for human resources? When people open the door to a mall, do they agree surveillance camera footage can train automated decision-making for criminal justice systems? Shifting data from one context to another raises concerns about the role of consent as an oversight mechanism. Do people attempting to provide consent after downloading an app understand how personal information might flow within an organization? For example, from the Loblaws PC Optimum program to the health and financial service companies within the Loblaw organization? From one organization to another, like from Foursquare mobile location tracking to KFC? In both scenarios, the answer is likely not if people aren’t reading terms of service and privacy policies.

Meaningful Consent and “The Biggest Lie on the Internet”

Meaningful consent suggests that individuals realize awareness and understanding of how personal information is used in the moment, as well as implications for the future. Developing this understanding can be difficult if AI developers refuse to teach people about industry practices, and impossible if people ignore opportunities for engagement and learning.

Noting about an “extractive logic” central to the way AI developers collect and use data, Crawford writes: “It has become so normalized across the industry to take and use whatever is available that few stop to question the underlying politics” (p. 93).

Those underlying politics include something referred to as “the biggest lie on the internet” known as “I agree to the terms and conditions” (see: www.biggestlieonline.com). This internet meme suggests people “lie” by accepting service terms without accessing, reading, or understanding them. The size (i.e. “biggest”) is due to the ubiquity of digital services, whose terms people accept all the time.

In two studies attempting to unpack “the biggest lie on the internet”, undergraduates and adults 50+ were presented with a fictitious online consent process for a made-up social media site. In both studies, participants consistently ignored and rushed-through the online consent process by either skipping policies without accessing them, or by spending little time reading them. To assess whether participants understood the implications of agreement, the service terms included “gotcha clauses”. In the undergraduate study, the service terms included a “first-born child” clause, requiring participants to give up a child to use the social media service. Of the 543 participants, 93% agreed. In the older adult study, 83.4% of 500 participants agreed to give up a kidney to use a similar social media service. In both studies, when asked if there was anything concerning about the policies, more than 98% of participants, in both studies, did not identify these problematic clauses.

If the people in the two studies could miss the gotcha clauses, and not identify two very extreme implications of so-called agreement, it is likely that they might also miss opportunities to learn about data sharing for AI development.

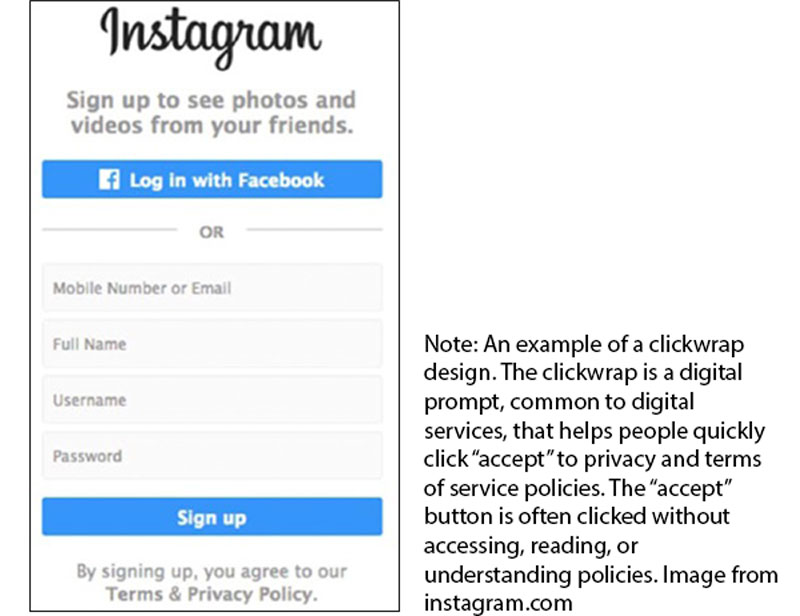

There are many reasons for “the biggest lie on the internet”, including the length and complexity of digital service policies, as well as the resignation and disinterest of the individual. Especially concerning is the clickwrap (see above), the front-gate to digital ecosystems shaped and harvested by surveillance capitalists and other AI beneficiaries. Instead of design innovations to support awareness and understanding, this deceptive user interface design encourages ignoring behaviours – speeding people through online consent processes and towards the parts of digital services that generate revenue.

Recommendations

The Canadian government appears to maintain the position that meaningful consent is fundamental to personal information protections. Consent is central to current privacy law and appears central to Bill C-27. But there is a considerable difference between implied or express consent and meaningful consent. Relying on implied consent facilitates a lack of organizational self-regulation, making it difficult for people to develop awareness of agreement implications, as there is a lack of notification that policy acceptance is occurring. Express consent, manifested often via clickwrap agreements is problematic as well, since research suggests (see video above) clickwraps encourage service term ignoring behaviours to the benefit of AI developers.

The only ethical way forward is meaningful consent.

Whether data for AI development is obtained directly from individuals or from another organization, any efforts connected to the building of AI must commit to ensuring information was obtained via meaningful consent. Organizations must improve online consent processes by addressing problematic clickwrap agreements. They must invest in thoughtful and engaging strategies for informing and educating the public about AI development. This will help people figure out the implications of agreement and reduce “the biggest lie on the internet”. Without these efforts, a future defined by artificial intelligence realized through a lack of public oversight, may deliver benefits to developers and investors, at the expense of individual oversight and civil liberties.

For more information, please visit www.biggestlieonline.com. Funded by the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada, the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council, and York University.

About the Canadian Civil Liberties Association

The CCLA is an independent, non-profit organization with supporters from across the country. Founded in 1964, the CCLA is a national human rights organization committed to defending the rights, dignity, safety, and freedoms of all people in Canada.

For the Media

For further comments, please contact us at media@ccla.org.