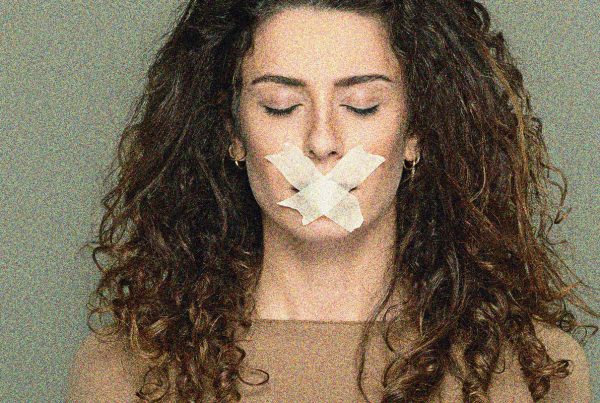

Helen Naslund, a 56 year old grandmother, was sentenced to 18 years in jail for manslaughter after killing her abusive husband while he was sleeping, and then hiding his body. This exceedingly long sentence is 16 years longer than the average sentence imposed for manslaughter by a woman of a male partner, according to a 2002 report. Helen’s sentence was decided within a criminal justice system that imposes mandatory sentences (and deters self-defence claims). And it seems to take minimal account of the trauma, threats, and very real dangers faced by women who live with intimate partner violence (also known as “battered women’s syndrome”).

These are the facts of Helen’s case, accepted by both her lawyer and the government lawyer who prosecuted her: Helen’s husband, Miles, had for over 27 years, been physically violent with her, and made comments to her that made her fear for her safety while he was heavily intoxicated and wielding firearms. Helen was depressed for years and made a number of suicide attempts, but did not feel she could leave the marriage due to the “history of abuse, concern for her children, depression, and learned helplessness.” On the weekend before she shot him, Miles became angry with Helen over a broken tractor, ordered her around while “handling his firearm,” and hurled wrenches at her. On the day she shot him, he threatened to make her “pay dearly,” and his threatening behaviour increased throughout that day. That night, Helen killed Miles while he slept. In the morning, she hid his body in a pond where it remained for six years while she misled police as to his whereabouts.

These too are facts: in Canada, on average every 6 days, a woman is killed by her intimate partner. Women with disabilities, Indigenous women, and queer women are subjected to increased rates of intimate partner violence.

Courts have for decades recognized battered women’s syndrome (BWS) as a subset of post-traumatic stress disorder. Some courts have explained women’s experience of the cycle of violence in terms of their fear, shame, terror and victimization that led them to pull the trigger. Courts have also recognized non-stereotypical, rational explanations as to why a woman might stay in an abusive relationship – to protect her children from abuse, limited social and financial support, and the lack of a guarantee that the violence would end if she left – and how her use of deadly force against her abuser, even outside the heat of a conflict, may have been reasonable to preserve her own life.

BWS has been used to support a claim of self-defense for women who have killed their abusers in “quiet” moments, such as when the abusive spouse was sleeping or not actively going after her. Yet to claim this defense in court, one has to go to trial and risk conviction. If convicted, currently, there is a mandatory penalty: life in jail without parole for 25 or 10 years for first or second degree murder, respectively.

Helen Naslund was charged with first degree murder. Faced with this terrifying risk, she pled guilty to manslaughter. Other women who have done the same then raised BWS as a factor that should lessen their sentence. However in Helen’s case, the plea bargain required her to also agree to the 18 year sentence. The prosecutor sought to justify this harsh penalty by delineating certain “aggravating factors” – factors that bear a painful resemblance to Helen’s own experience over 27 years of abuse. First, he argued, “…this offence involved an intimate partner and position of trust. Second, it involved the use of a firearm. The reasonable foreseeability of harm with a firearm involved is obviously greater. Number three, this occurred in the victim’s own home, a place where he’s entitled to feel safe.” The irony – and injustice – of these arguments was apparently lost on the prosecution.

The prosecutor did also set out other “aggravating factors” with respect to how Helen had disposed of Miles’ body, and her efforts to deceive police about what she had done, however none of these justified the lengthy sentence imposed.

BWS is a legally recognized doctrine that should be available to women who, after years of abuse, are highly attuned to escalating violence and threats, and may in a critical moment act to preserve their own life, even if outside a heated exchange. Statistics about the number of women killed by their intimate partners crystallize the very real threat faced by women like Helen.

The prosecutor had the authority all along to lower the charges against Helen to manslaughter, or to strike a different, more humane bargain that recognized the dangers she had faced.

And the sentencing judge had the power, in extraordinary circumstances like these, to override the plea bargain’s terms and reduce the sentence. Instead, he offered her a word of sympathy stating: “Although I have empathy for … you, this requires a stern sentence…Deterrence is the main principle of sentencing that has to be looked at, deterrence and denunciation …”. Then he sentenced her to 18 years in prison.

Battered women’s syndrome allows us to question the goals of the criminal justice system when faced with the violence women are subjected to in society. Ultimately, courts and government should be spending more time on deterring this violence; on building a society in which women are deemed equal and can exist without threats to their security.

Helen’s case is one damning example of the dangers of mandatory minimum sentences.

Perhaps what needs to be denounced is not solely Helen’s act, but the systems of policing, social security, and gender norms that allowed her subjugation to violence for 27 years going unquestioned.

Perhaps what needs to be denounced is a justice system that could allow for a plea bargain that imprisons a survivor of abuse to 18 years.

Perhaps what needs to be denounced is a justice system that appears inadequate to represent the complex lived experiences of people before the law.

Noa Mendelsohn Aviv (CCLA Equality Director) and Kassandra Neranjan (CCLA Legal Volunteer, McGill Law Student)

About the Canadian Civil Liberties Association

The CCLA is an independent, non-profit organization with supporters from across the country. Founded in 1964, the CCLA is a national human rights organization committed to defending the rights, dignity, safety, and freedoms of all people in Canada.

For the Media

For further comments, please contact us at media@ccla.org.