June 10, 2021

Today Canada’s Privacy Commissioner released the Special Report to Parliament on Police Use of Facial Recognition Technology in Canada, finding that Canada’s national policing body, the RCMP, were not in compliance with the Privacy Act when they acquired and used Clearview AI facial recognition technology. RCMP dispute they violated the Act, apparently taking the position that it would be unreasonable for them to assess vendor compliance with Canada’s laws and that s. 4 of the Privacy Act does not technically require them to do so.

Clearview AI is an American facial recognition vendor that became widely known in January 2020, when a New York Times investigation revealed that the company scraped 3 billion photos of people from the internet, created a facial recognition system to exploit that database, and is marketing access to police forces globally.

This is the second investigation relating to Clearview AI conducted by the Office of the Privacy Commissioner. In the first, under Canada’s private sector privacy law, known as PIPEDA, the scathing investigation report stated that Clearview used billions of people’s images for an inappropriate purpose: “the mass collection of images…represents the mass identification and surveillance of individuals by a private entity in the course of commercial activity” for purposes which “will often be to the detriment of the individual whose images are captured” and “create significant risk of harm to those individuals, the vast majority of whom have never been and will never be implicated in a crime.”

Given the direct findings of illegality in the initial investigation under PIPEDA, CCLA has been waiting to see if this investigation would answer the serious questions that arise from police use of this technology, including how Canada’s national policing agency made the decision to use the technology, and why any internal analysis failed to raise a red flag about legal compliance. Today’s investigation findings, made under the federal public sector Privacy Act, reveal a pattern of obfuscation on the part of the RCMP (for example, RCMP said they used Clearview 78 times, but Clearview records show it was 521) and failure to comply with simple procedures, such as a Privacy Impact Assessment requested by the OPC. They further show the RCMP doubling down on a particular interpretation of the law (written long before FRT was developed) to try to avoid acting accountably with due consideration for Canadian’s privacy rights when offered a technology that holds promise for their work but carries even more significant risks for people in Canada when it is used. The RCMP did ultimately agree to abide by the Commissioner’s recommendations, including creating better legal compliance assessments and stronger oversight when acquiring novel data-driven technologies.

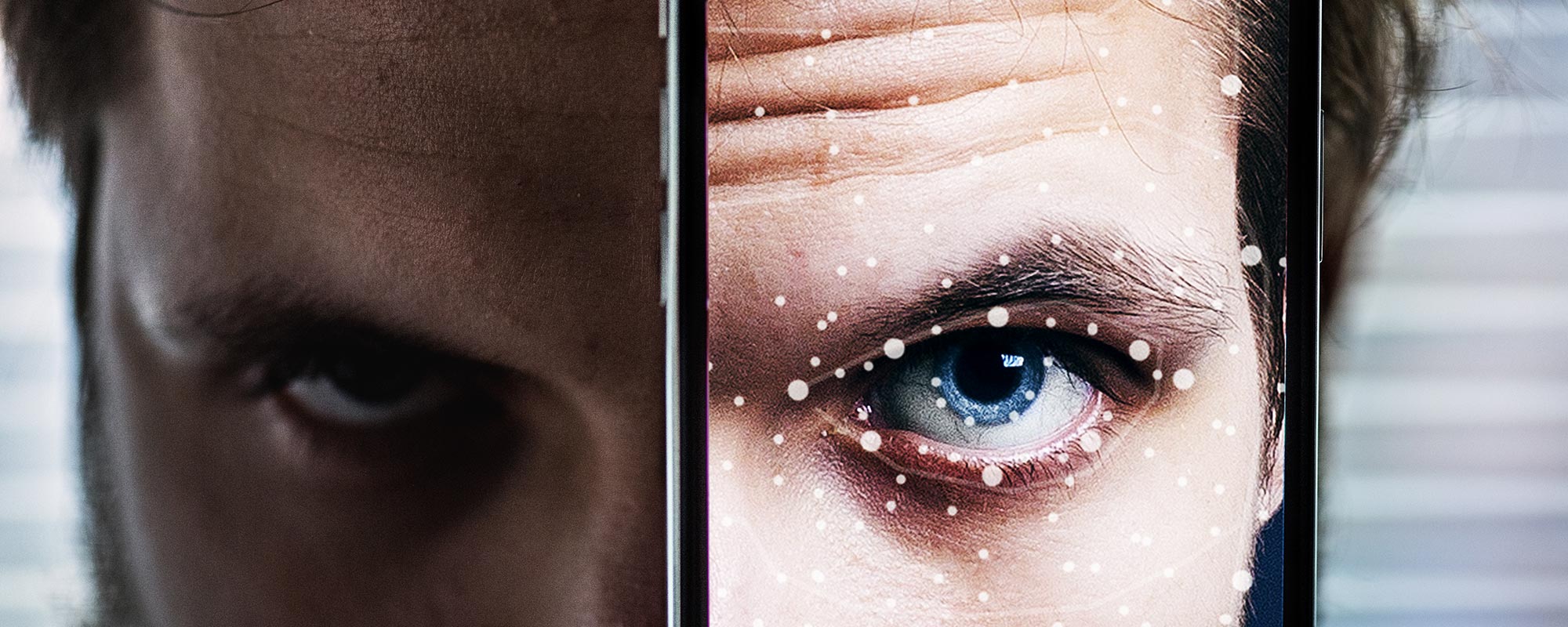

People in a democracy need protection from untrammeled facial recognition because it is a threat to human freedom, pure and simple. Facial recognition uses the physical characteristics of our face to create a mathematical model that is unique to us, that identifies us, just like a fingerprint. It is an identifier inextricably linked with our body, that can be collected from a distance and without our knowledge or consent. Taken to extremes, facial recognition let loose on our streets would mean the annihilation of anonymity, a complete inability to move around the world and be a face in the crowd. It would fundamentally change the relationship between residents and police, if police have the power to covertly identify anyone and everyone, at will and without restriction. And of course, given the known flaws in the technology which is less accurate of faces that are Black than white, male than female, middle-aged than young, there are huge equality implications.

Police cannot be above or beyond the law, and internal, behind-the-scenes interpretations of the law must not be allowed to guide acquisition of invasive surveillance technologies, particular given the absence of meaningful accountability or transparency provisions when it comes to police surveillance.

There’s a public debate that desperately needs to happen around tools of mass surveillance, about the risks of using indiscriminate information capture about everyone to catch the very few bad guys in a sea of innocent bystanders going about their lives. But what the Clearview AI story tells us is that there is an equally urgent debate we need to have about accountability when it comes to police surveillance. Necessary, fundamental questions about necessity, proportionality, and legality don’t get asked and answered publicly, however, when police surveillance technologies are procured and used in secret, as was the case with Clearview AI.

Police often argue that it compromises their work if the investigative tools they use are known to the public. However, social license to exercise the powers we grant our law enforcement bodies can only exist in a trust relationship, and before we even get to the question of whether or not there is social benefit in allowing police to use the technology and if so, whether it outweighs the social risks, we need assurance that our law enforcement bodies are committed to using tools that are lawfully conceived and lawfully implemented. This investigation is a call for change. The FRT use guidelines and consultation planned by the OPC will provide an essential opportunity for people across Canada to begin conversations about what that change must look like. CCLA is committed to working to help that change happen.

About the Canadian Civil Liberties Association

The CCLA is an independent, non-profit organization with supporters from across the country. Founded in 1964, the CCLA is a national human rights organization committed to defending the rights, dignity, safety, and freedoms of all people in Canada.

For the Media

For further comments, please contact us at media@ccla.org.